Conflicting Clues

I’ve adapted Amy Johnson Crow’s 52 ancestors in 52 weeks challenge.

Each week’s post follows my children’s ahnentafel numbering, which determines the featured ancestor.

This ensures no one until mid-sixth generation gets left behind.

52 Ancestors in 52 Weeks: 2026 Week 09: Conflicting Clues

Introduction

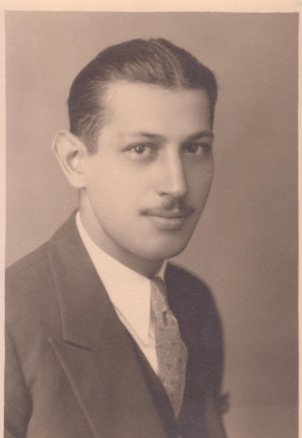

My assigned Week 9 ancestor is Anna Brenda FRANK BIRNBAUM.

And “Conflicting Clues” turned out to be a particularly instructive one.

Was Anna a U.S. citizen?

Discussion

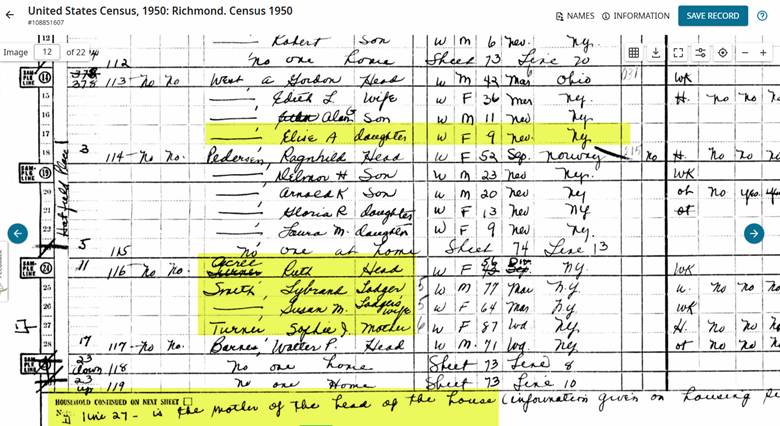

Anna was born in New York City in 1889. While I haven’t found her birth record, I have found her siblings’, and I have her with her family in the 1900 and 1905 censuses. She married Samuel Birnbaum, an immigrant, in 1906.

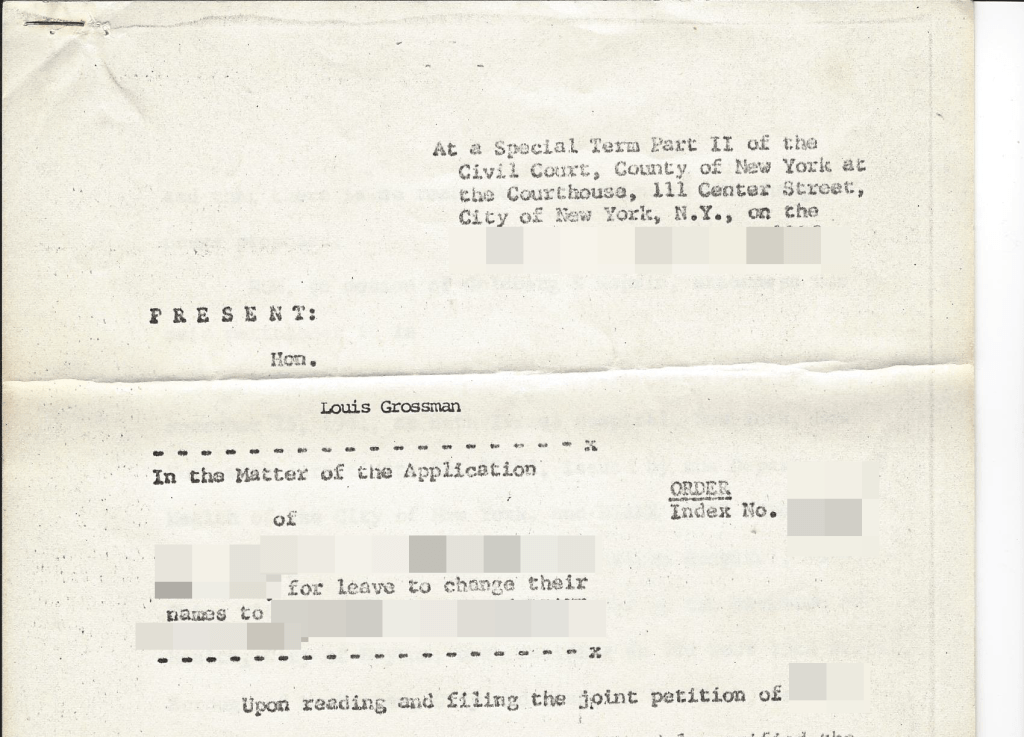

The following year, the 1907 Expatriation Act automatically revoked the citizenship of women who married non-citizens. Suddenly many women who had grown up here and never seen a ship were aliens.

Because Anna married in 1906, just before the law took effect, she may have narrowly avoided this automatic expatriation.

Imagine what that was like for them. Did it affect them socially? Did they feel disenfranchised from a place that had been their home for perhaps decades? And what would the consequences be? The act remained in place until the early 1920s – right around the time women gained the right to vote. Imagine fighting for suffrage only to learn your marriage disqualified you?

Imagine if I had seen Anna in 1910 listed as an alien and thought, “Well, that’s not my Anna.”

So, the moral of the story is, as Judy Russell, The Legal Genealogist, keeps reminding us, to know the laws in effect in the time and place of the event.

The law was largely (but not completely) repealed by the Cable Act of 1922. (Asians were still discriminated against.)

The National Archives has a helpful PDF at When Saying “I Do” Meant Giving Up Your U.S. Citizenship.

Challenge

Reexamine your no-brainers and look for incongruities which may have escaped notice previously. Investigate why!

You can look for:

- Citizenship shifts

- Border changes

- Age discrepancies

- Marital status laws

What conflicting clues are you dealing with?

Created with AI

AI Disclosure

This post was created by me with the help of AI tools. While AI helps organize research, the storytelling and discoveries are my own.

Next Week’s Topic: Changed My Thinking