I’ve combined Amy Johnson Crow’s 52 ancestors in 52 weeks challenge, and Steve Little’s The 2025 AI Genealogy Do-Over, to create a unique 52 AI ancestors in 52 weeks party!

52 AI Ancestors in 52 Weeks: Week 50: Family heirloom

Introduction

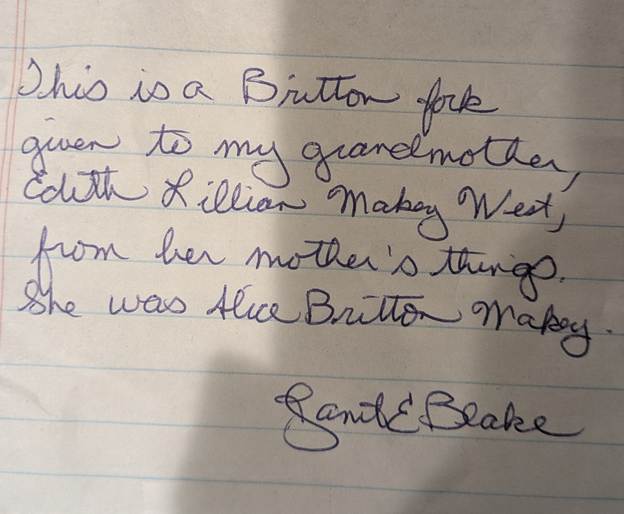

My grandmother, Edith Lillian MAKEY WEST (1913-1997)’s mother was a BRITTON, who died when Grandma was just 3 years old.

When Grandma’s dad was widowed, he sent the children to live with his wife’s sister until he remarried, about 2 years later. This was just part of a long and enduring closeness in the family – Grandma always spoke fondly of Aunt Edith (her namesake), who never had children of her own.

Discussion

I strongly suspect it was Aunt Edith who, in the absence of a mother, helped Grandma to feel close to her maternal family and line. Grandma was always proud to be a Britton and always wondered if she was part of the old Staten Island New York BRITTON line (spoiler: she was). Grandma inherited many old family photos which I am now fortunate to have – a few of them identified, many tentatively identified, and some a mystery to this day.

I think it was this effort at connection that made the “B” forks that Grandma inherited extra precious to her. She proudly passed them on to me. I put one in a shadow box and proudly hung it up on display. (With a detailed label in the back, of course!)

When my future daughter-in-law came to visit, she was so nervous she accidentally knocked the shadow box off the wall. It came apart slightly, but I put it right back up. I’ve never fixed the crack. It’s a quiet reminder that all of us carry flaws – and we’re still worth displaying. Who knows, someday I may pass those forks down to her.

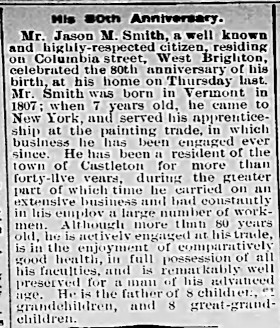

Figure 1 Private collection of the author, photographed 2025

How AI Can Help

We often think of artificial intelligence as something high-tech and hands-off—but sometimes, it’s as down-to-earth as helping us label a fork.

Take this handwritten note, for instance. It tells the story of a simple family fork passed down through generations—from Alice Britton Makey to Edith Lillian Makey West, and eventually to me. It’s personal, precious, and easily lost in the shuffle of old photos, papers, and drawer ephemera.

Figure 2 Label from Britton fork, photographed December 2025. Private collection of the author

That’s where AI comes in.

1. Reading Handwriting

Using free apps or tools like Google Lens, Microsoft OneNote, or even genealogy-focused AI tools like Transkribus, you can snap a picture of a handwritten label like this one. AI can then transcribe it, turning it into searchable text. Suddenly, “This is a Britton fork…” becomes something you can find in your digital files, even if you forgot which folder you stashed it in.

2. Creating a Digital Heirloom Catalog

Once your handwritten notes are transcribed, AI can help catalog your heirlooms. Pair the text with a photo of the object and upload both to:

- Google Photos (with searchable tags)

- FamilySearch’s Memories section

- A private blog, shared album, or even a spreadsheet

Some AI tools (like Notion AI or Mem.ai) can also help you organize stories, people, and photos; linking objects with relatives, dates, and locations.

3. Finding Hidden Clues

AI can help you recognize names, places, and patterns you might miss. Is “Alice Britton Makey” showing up in census records you hadn’t noticed? Does the handwriting match other letters in your collection? With a little help, AI can connect the dots across generations – and across the pages in your shoebox.

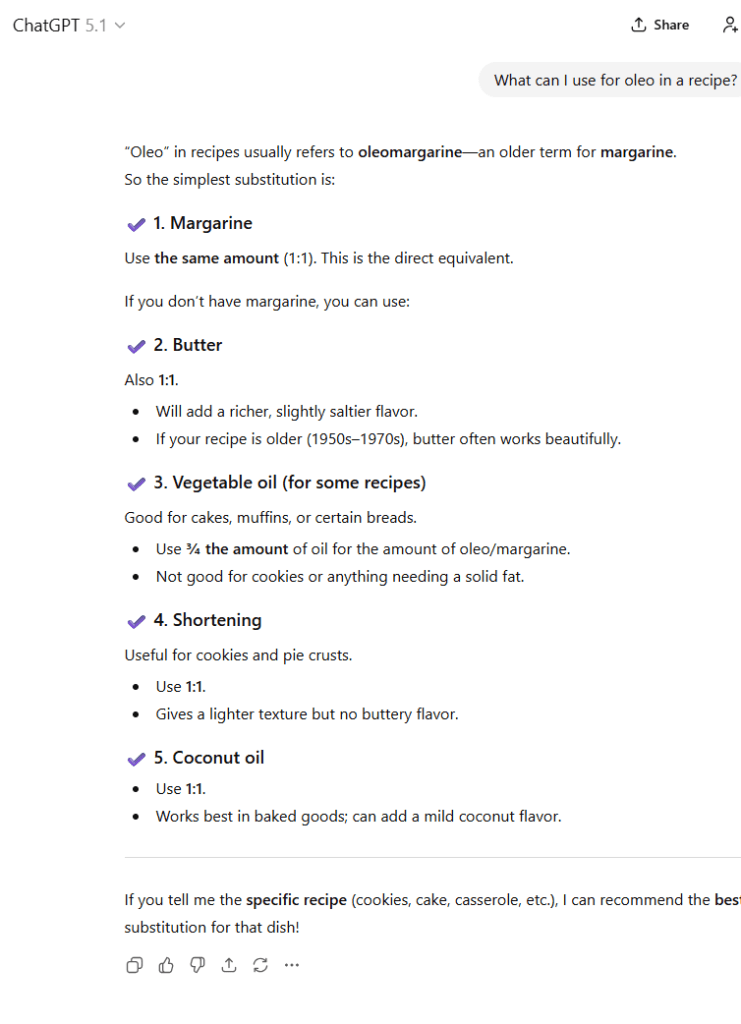

4. Let AI Help You Cite Your Sources

I highly recommend Dr. Tom Jones for citation help – one of his courses, or his book Mastering Genealogical Documentation. But, if I may be blunt, a half-assed sourcing is better than no sourcing. Just do it! Let AI help you create a source citation: ask for one in the style of the Chicago Manual of Style (which genealogical citations are based on). Tools like ChatGPT or Claude can take your messy notes and return a decent first draft. It’s not cheating, it’s documenting smarter.

Challenge for Readers

This week, try this:

- Take a photo of a label, note, or handwritten item from your collection.

- Use a free app (like Google Lens or OneNote) to convert it into text.

- Pair the text with a photo of the item in a digital file or document.

Bonus round: Ask AI to suggest which ancestor the item might belong to based on names mentioned in the text. You might get a match you hadn’t considered.

Want to Learn More?

Cataloging Ephemera & Heirlooms

Whether it’s a fork, a photograph, or a funeral card, ephemera deserves a safe, searchable home. These tools and guides can help:

- FamilySearch Memories – A free space to upload photos, documents, and heirloom stories. Connects to your family tree. https://www.familysearch.org/memories

- Google Photos – Use searchable tags and facial recognition to keep track of who’s who and what’s what. Great for visual cataloging.

- Notion or Airtable – Create your own digital heirloom tracker with images, tags, and notes. (For spreadsheet lovers and chaos wranglers.)

Citing Genealogical Sources (Without the Fear)

If you’ve ever stared at a census record and wondered, “How exactly do I cite this without summoning Elizabeth Shown Mills in a puff of citation smoke?”, you’re not alone.

- Evidence Explained by Elizabeth Shown Mills – The gold standard for genealogical citations. Not just for academics. Her companion website is a treasure trove of citation models and how-tos. https://www.evidenceexplained.com

- FamilySearch Wiki: Source Citations – Beginner-friendly and surprisingly thorough. https://www.familysearch.org/en/wiki/Source_Citation_Guide

- Cite-Builder Tools – Some genealogy sites like Ancestry and MyHeritage now offer automatic citation builders. Use with care, and a grain of salt. They’re generally better at citing the record group than your individual find.

And don’t forget: your heirloom’s story is a source. If you’ve got a label, inscription, or oral history, document where it came from. “Private collection of the author, scanned in 2025” goes a long way toward future-proofing your family archive.

Next Week’s Topic

“Musical”

AI Disclosure

This post was created by me with the help of AI tools. While AI helps organize research, the storytelling and discoveries are my own.

![An obituary for Stephen Barker, mentioning that he was shot "in the riots of 1862[sic]"](https://theancestorwhisperer.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/image-1.jpeg?w=624)