I’ve combined Amy Johnson Crow’s 52 ancestors in 52 weeks challenge, and Steve Little’s The 2025 AI Genealogy Do-Over, to create a unique 52 AI ancestors in 52 weeks party!

52 AI Ancestors in 52 Weeks: Week 41: Water

A canal boat from Philly to northwest Ohio: fact or fiction?

Introduction

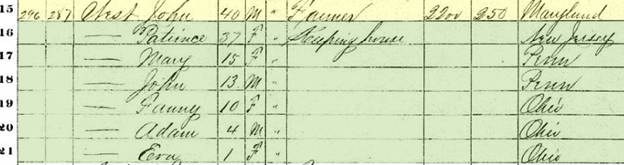

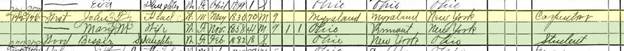

Sometimes we are lucky enough that a family story is passed down: my grandfather’s sister Lydia Coral West did family history work and my uncle Alan G West wrote up her facts. Part of the writeup states that John Thomas WEST and his wife Patience P. SPIEGLE moved [from Philadelphia] to northwestern Ohio “by canal boat”:

How can we research the veracity and details of these stories?

Discussion

I have studied maps and am not clear how a canal boat could be used to go from Philadelphia to northwestern Ohio. Google search helped me, though.

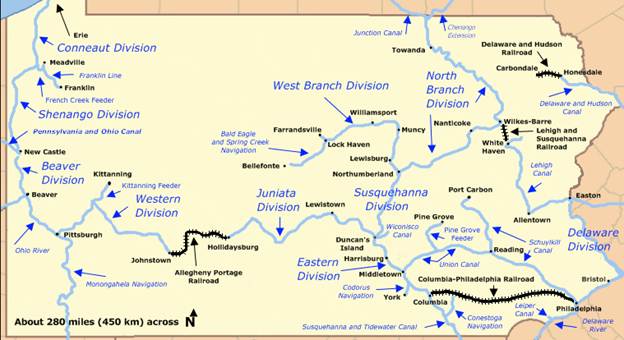

Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania had a complex canal system in the 19th century, and it was entirely possible to travel from Philadelphia to Lake Erie via water and some portage.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pennsylvania_Canal

Ohio: First, to locate the target location. The story says they landed in “Damascus, in north western Ohio.” But Damascus Ohio is landlocked in eastern Ohio. However, a further Google search informs us of “a former town called Old Damascus in Northwest Ohio that was replaced by a new bridge over the Maumee River.” My grandfather grew up around the Maumee River, so now I know we are talking. But later searches showed me a better candidate – Damascus, in Henry County, just across the Maumee from what was or would become Liberty Center, where three generations of my ancestors lived.

https://ohiomemory.org/digital/collection/p267401coll32/id/15560/

Between the canals that these two states had to offer, it is clear that the trip was entirely possible. Every fact in that particular written history has proven true so far, and this follows the pattern. (Don’t get me started about my OTHER side, where I was able to DISPROVE everything I was told…)

How AI can help

I chose Gemini because it surely can call upon Google maps and Google searches for an assist here.

Can you tell me how my ancestors might have traveled from Philadelphia, Pennsylvania to Damascus, Henry County, Ohio, via canal boat in 1858?

(Kindly note that this was a refined prompt, not my first one, and know that “few-shot prompting” is a valuable tool in the toolbox. You should rarely take the first answer.) What I received was absolutely fascinating:

The journey from Philadelphia to Damascus, Henry County, Ohio, via canal boat in 1858 would have been a long, multi-system voyage that crossed the entire width of Pennsylvania and traversed nearly the full length of the Ohio canal network.

By 1858, the “golden age” of canals was over, and the state-owned canals in Pennsylvania had just been sold to private interests. However, canal boat travel, especially for moving household goods and for travelers with limited funds, was still an option.

Here is the most plausible canal boat route your ancestors would have taken:

Phase 1: Across Pennsylvania (Philadelphia to Pittsburgh)

The first challenge was crossing the Appalachian Mountains. This required a mixed-mode transportation system known as the Pennsylvania Main Line of Public Works, which was a series of canals and railroads designed to link Philadelphia to the Ohio River at Pittsburgh.

- Philadelphia to Columbia, PA: They would have started by taking the Philadelphia and Columbia Railroad (a steam-powered railway) about 80 miles west from Philadelphia. By the 1850s, the railroad had generally replaced the earlier canal sections near the city for passenger travel.

- Columbia to Hollidaysburg, PA: From Columbia, they would switch to a canal boat on the Eastern Division of the Pennsylvania Canal, traveling up the Susquehanna and Juniata Rivers to Hollidaysburg.

- The Allegheny Portage Railroad: At Hollidaysburg, the boat or its cargo would be transferred onto special flatbed railcars to be hauled over the Allegheny Mountains to Johnstown, PA. This was a 36-mile incline plane and railroad system that served as the necessary land bridge.

- Johnstown to Pittsburgh, PA: Once on the western side, they would re-enter the water via the Western Division of the Pennsylvania Canal and float down the Conemaugh and Kiskiminetas Rivers to the terminus in Pittsburgh on the Ohio River.

Phase 2: Connecting to the Ohio Canal System (Pittsburgh to Akron/Cleveland)

At Pittsburgh, they would need to find a connection to the canals leading into Ohio.

- Pittsburgh to New Castle, PA: They would take a boat north up the Beaver Division of the Pennsylvania Canal to reach New Castle, Pennsylvania.

- New Castle to Akron, OH: Here, they would transfer onto the Pennsylvania and Ohio (P & O) Canal (also known as the “Cross-Cut” Canal). This canal ran 82 miles and connected New Castle to Akron, Ohio.

Phase 3: Across Ohio (Akron to Damascus, Henry County)

Akron served as the hub of the Ohio canal system, connecting the P & O Canal to the major north-south artery: the Ohio and Erie Canal.

- Akron to Toledo, OH: Your ancestors would board a boat on the Ohio and Erie Canal and travel north toward Lake Erie to the city of Toledo.

- Toledo to Damascus, Henry County: In Toledo, the Ohio and Erie Canal merged with the Miami and Erie Canal. They would change boats onto the Miami and Erie Canal to travel southwest toward their destination.

- Damascus is located in Henry County, situated directly on the Miami and Erie Canal, near the town of Napoleon, Ohio. The boat would pass through or near the town of Junction, Ohio, where the canal system was connected to the Wabash and Erie Canal.

- Their canal boat journey would end when they disembarked at the closest landing point to Damascus, likely at a canal town like Napoleon or another landing in Henry County.

The Journey Experience and Duration

This route was a major undertaking, likely covering over 600 miles and involving multiple boat changes, a railroad section, and many locks.

- Pace: Canal boats, pulled by mules on the towpath, averaged a slow but steady pace of about 4 miles per hour, moving approximately 30 to 40 miles per day.

- Total Time: Factoring in the delays for transferring to the Portage Railroad, waiting for boat transfers, and navigating hundreds of locks, the complete journey would have taken a minimum of 3 to 4 weeks.

- 1858 Context: By this time, railroads were faster and were heavily competing with (and replacing) the canals. While the canal route was still operating and was cheaper, your ancestors may have faced delays due to deteriorating infrastructure or chosen to use faster, parallel railroad lines for certain segments, especially across Pennsylvania, to shorten the overall travel time.

Can you create a map of this route?

The result was a little disappointing, but further prompting revealed that Gemini could not create a historical map, which makes sense, and it could not sufficiently interact with an existing historical map in order to mark it up for me.

Knowing that a young couple with two young children made this arduous journey gives me a healthy respect for what people will do for opportunity.

Tracing this journey showed me that what seemed like family folklore was entirely plausible, with stops, transfers, and towpaths all lining up. A young family could have realistically made the canal-heavy trek from Philadelphia to northwest Ohio in the late 1850s, likely taking several weeks. AI didn’t replace the research; it simply helped me ask better questions and find new leads. What began as a passing reference in a family write-up became a full-fledged route through history.

Challenge for Readers

Think about the water in your ancestors’ lives.

- Did they work on rivers, canals, or ships?

- Did they settle near lakes or ports?

- Can you trace their movements using historic waterways or maps?

Try plugging one ancestor’s location and time period into an AI tool like ChatGPT or Gemini with a question like:

“How could someone have traveled from [Location A] to [Location B] in [Year] using canals, rivers, or railroads?”

Then see what splashes up!

Bonus: If a story in your family lore involves water (a flood, a sea voyage, a ferry, etc.), investigate it. Was it possible? What would it have felt like?

Have you ever traced an ancestor’s route? I’d love to hear how your research flowed.

Want to Learn More?

- The Pennsylvania Canal on Wikipedia – A detailed history of the route.

- Ohio Memory – Miami and Erie Canal – Visual archives and canal history.

- Try AI tools like ChatGPT or Gemini to “roleplay” as 19th-century travel assistants! Prompt them with: “Pretend you are a canal boat captain in 1858. How would you get a family from Philadelphia to Henry County, Ohio?”

Next Week’s Topic: “Fire”

AI Disclosure

This post was created by me with the help of AI tools. While AI helps organize research, the storytelling and discoveries are my own.