I’ve combined Amy Johnson Crow’s 52 ancestors in 52 weeks challenge, and Steve Little’s The 2025 AI Genealogy Do-Over, to create a unique 52 AI ancestors in 52 weeks party!

52 AI Ancestors in 52 Weeks: Week 21: Military

Three Wars, Four Stories: A Family’s Legacy of Service

Introduction

It starts with a name on a gravestone. Or an old photo of a young man in uniform. My family’s military story stretches across nearly 200 years, from militia musters to wartime telegrams and folded flags.

This post is about four relatives—each touched by military service—whose lives reflect how war, and the people who fight it, have changed over time.

Discussion

Part I: The Militiaman (Revolutionary War)

Henry Denny (1758-1839) wasn’t a soldier, not in the professional sense. He was a hatter with a musket and a sense of duty. My Revolutionary War ancestor served in the local militia, answering the call when British troops threatened their region. His records are sparse—a muster roll here, a pension application there—but they remind me that early American soldiers were ordinary citizens first, reluctantly drawn into extraordinary times.

Henry Denny served “during the whole of said [Revolutionary] war,”[1] according to his son’s declaration for his father’s pension. He was a Sergeant in Captain John Outwater’s regiment in Bergen County, New Jersey and on one occasion “was wounded by a hessian rifleman”[2] and another time defended Hackensack when the enemy tried to burn it down. Outwater’s sons made depositions to Henry’s service, one of them saying, “Henry Denny and Sylvester Marius (now dead) were two men on whom he could depend … a faithful soldier”[3] and Outwater’s nephew stating that Henry “was brave and unflinching in the cause of his country, a clever, honest man, and a good soldier.”[4]

Figure 1 From Henry Denny’s pension file, not successful until Outwater’s records were located after Denny’s death.

Service then was seasonal, often local, and deeply tied to one’s community.

Part II: The Soldiers (Civil War), or, Patience’s sacrifice

Fast-forward nearly a century. Another ancestor, John Thomas West, husband of Patience Spiegle, wore Union blue, enlisted in the thick of the Civil War, and was posted to a prison camp: Johnson’s Island, in Ohio.

John served as a Private in Company C of the 128th Ohio Volunteer Infantry, from Independence day in 1863 until after the war ended.

Figure 2 John Thomas West (1830-1924)

John lived to come home—but his brother in law did not.

Patience’s brother, William Speagles, enlisted in the 12th New Jersey as a Private on August 13, 1862 at the age of 17 (saying he was 18), an orphan. He marched, camped, and fought in places now etched in bronze plaques and field trip itineraries. He was wounded in Cold Harbor and died in a field hospital a week later. His belongings (clothing, thread needle roll, pictures, memorandum book, gold ring, gold pen holder, “Testament”) were sent to his sister Hannah. He was buried in the National Cemetery in Alexandria, Virginia, but I believe he was reinterred to his home state at some point.

Figure 3 A casualty ledger showing William P. Speagles

This war was industrial, brutal, and personal. The letters home were fewer, the distances longer, and the weapons deadlier. These men were part of enormous, impersonal armies—but still deeply rooted in their towns and families.

Service had become more organized, more dangerous, and far less optional.

Part III: The Fallen Cousin (World War II)

He was just 24. A cousin whose name I only knew through whispered family stories until I found his records. Killed in action overseas in World War II, his death sent ripples that are still felt today. Unlike the earlier wars, this one pulled Americans onto a truly global stage. His body never came home, but his photograph, his name on a memorial, and the folded letter to his parents keep him present.

Private Robert J. Anderson (1920-1944), a first cousin to my grandfather, served in the 116th Infantry Regiment, 29th Infantry Division, which was one of the first on the beach on D-Day. Their backup didn’t make it, and they suffered heavy losses. After D-Day, they went across France, liberating the towns. It was in St. Lô that Robbie was killed. They say (source unknown):

The 29th took five weeks to reach St. Lo. Just before the final drive captured the city Maj. Thomas Howie, commander of the 3d Battalion, 116th Infantry, promised his men “I’ll see you [at] St. Lo.” He was killed immediately afterwards but General Gerhardt ordered the column to carry his body into the town square. A New York Times correspondent’s story of the incident immortalized the “Major of St. Lo.”

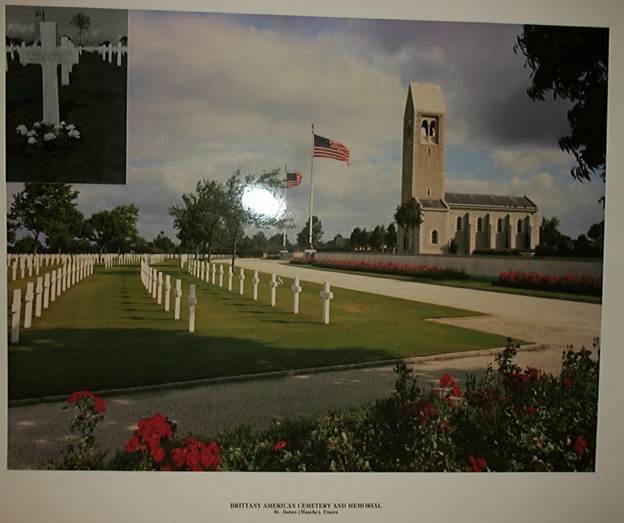

Robbie was posthumously awarded the Purple Heart and is buried at the Brittany American Cemetery outside St. James, France.

Figure 4 Robbie’s burial site, kindly sent to me by the American Battle Monuments Commission

Service now meant a world war, mechanized death, and sacrifice at a scale families still struggle to reckon with.

Part IV: The Thread That Ties Them

Each of these relatives served in different wars, in different centuries, and under vastly different circumstances. But what unites them is a quiet sense of duty—not necessarily to “country” in the abstract, but to their neighbors, families, and values. The idea of service changed over time—from informal militias to massive military bureaucracies—but the personal cost never stopped being personal.

How AI can help

How AI Can Help With Military Research

Researching military ancestors used to mean squinting at microfilm or decoding government forms from 1863. Good news: AI can help with that—without stealing the fun of discovery.

Here are a few ways it lends a hand:

Translate That Handwriting

Found an old pension file or draft card full of spidery handwriting? AI tools can help transcribe or summarize these documents. You can even upload scans into some AI platforms and ask, “What is this telling me?”

Build a Timeline with background information

If your ancestor served across several battles or regiments, AI can help you turn scattered dates and places into a readable timeline—with historical context built in. Just feed it your notes, and ask for a summary. AI can give you quick background info so you don’t get lost in research rabbit holes.

I do need to mention Researcher here, which Microsoft revealed this month as part of Copilot. In my test runs, it does a great job starting your research.

Make Sense of the Story

Have some facts but not sure how to thread them into a narrative? AI can help you outline your blog post, suggest titles, or smooth out transitions—without rewriting your voice. You stay the storyteller. AI is the editor that never takes lunch.

Want to try it? Copy this into your notes:

“Here’s what I know about my ancestor who served in [war]. Can you help me understand what these records mean and how I might tell their story?”

You’ll be surprised by what unfolds.

Summary and challenge

From colonial militiaman to World War II casualty, my ancestors’ stories mirror the evolution of American military service. Their paths—marked by dusty muster rolls, battlefield graves, and pension papers—remind me that history isn’t abstract. It’s inherited.

Three wars. Four stories. One family.

Your Turn: Challenges for the Curious

Want to explore your own family’s military history?

Challenge 1:

Check Fold3.com or the free NARA archives for pension files, enlistment records, or draft cards. Even one document can tell a rich story.

Challenge 2:

Compare military service across generations in your family. How did roles, reasons, or outcomes differ? Make a simple timeline to trace the shift.

Next week’s topic: “Reunion.“

Disclosure

This post was created by me with the help of AI tools. While AI helps organize research, the storytelling and discoveries are my own.

[1] “Revolutionary War Pension and Bounty-Land Warrant Application Files,” images online, footnote.com (https://www.fold3.com/file/16580523 : accessed 23-Sep-2008) page 3; citing The National Archives, M804, Washington, D. C..

[2] Ibid, page 8

[3] Ibid, page 14

[4] Ibid, page 18